Hi y’all! Book Notes is back! If you don’t know how you got here, you probably signed up through my Instagram.

Here’s a link to the initial review I wrote of Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl. You can purchase the book here. You don’t really need to read it to understand what I’ve written in this post, but it may provide some useful context to what the fuck a Young-Girl is.

From Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl:

The Young-Girl’s every experience is drawn back incessantly into the preexisting representation she has made for herself. All of the overwhelming concreteness, the living part of the passage of time and of all things are known to her only as imperfections, as alterations of an abstract model… The Young-Girl is steeped in deja-vu. For her, the first time experience is always the second time representation.

A lot of the book talks about this idea, this unspoken need that the Young-Girl has of her life (herself) to conform to a particular “representation” (what I would call “narrative” but I suppose could even be “identity”), that all information/self-knowledge must be filtered through. A few things immediately came to mind when reading this. First, I thought of how many nights I’ve drunkenly and unsuccessfully argued “the importance of narrative” in our day to day understanding of ourselves and the world. And second, I thought about all those TikToks I see where teenagers talk about “main character vibes.”

The main character TikTok trend seems to have really taken off with this one audio, a voiceover of a girl talking over twinkling harp strings:1

You have to start romanticizing your life. You have to start thinking of yourself as the main character. Because if you don’t, life will continue to pass you by. And all the little things that make it so beautiful will continue to go unnoticed. So take a second, and look around, and realize that it’s a blessing for you to be here right now.

And users took that audio and layered it over all videos2 of themselves being Romantic and Picturesque and Hot (ie, the main character). And from there, it sort of became a meme. For example: if someone wants to make a self-deprecating joke, they won’t call themselves a narcissist, they’ll say they have “main character syndrome.” Or if someone looked really cool in a video (like, a hot hipster girl on a skateboard singing along to Grease), people might comment “you ARE the main character” (it’s not mocking or mean to tell someone else they are the main character. That’s flattering).

The main character is the person whose sadness is the most poignant, whose joy is the most unencumbered, who is cool, who is casually Romantic, who is alone but unknowingly watched (by an audience who both identifies with and aspirationally admires the main character).3 The main character is beautiful, but she doesn’t know it, like that One Direction song. The main character is mysterious. The main character takes long solo walks down his street in casually chic clothes, listening to The Shins. The main character looks pensively at an abstract sculpture in a sunny gallery. The main character doubles over with laughter surrounded by her best friends around a bonfire on a moonlit beach. His secret talent or hidden depths amaze the select few with good taste and judgement, people who really matter, not the unwashed masses. Her life might be saturated, or tinted, or black and white, but it is always carefully lit. The main character is the focus of an image or video. The main character is observed, never inhabited.

Of course, we all are, literally, the main character in our own lives. We see the world filtered through our own subjectivity, and I don’t think it’s wrong to say that we’re mostly concerned with ourselves (which isn’t on it’s own a bad thing). But we’re the main character of books written in the first person. TikTok users want to be the main characters in the third person. The main characters of invisible audiences, of movies.

Here’s one TikTok that got sorta popular.4 The user talks about how she’s “figured out how to attain self-love” by adding “sappy” music to videos of herself. Roll the clip: a montage of cute, candid moments, all focused on this user. She’s giggling and unstudied, but the editing is precise and there’s a gloomy, grainy blue filter that gives it this nostalgic vibe, like it’s from the 90’s. A man’s husky voiceover says, “I’ve never met anyone else like you, and I don’t think I ever will.” It sounds (and looks) like something from a movie. She notes in the comments that this is an example of her “main character complex.” It pretty much lays clear what was always evident: being the main character isn’t finding “little things” beautiful, it’s finding yourself beautiful.

The video achieves this strange distance from the user herself. The filters (blue, grainy, gloomy, vintage) age the video, like a flashback. The montage style itself lends a distancing of time too—after all, we’re getting a lot of different clips, from a lot of different days, so presumably, this is a fairly large period in time we’re looking back on (so, perhaps in a somewhat distant past). The voice over is disembodied, decontextualized. We know she made this of herself, that the audio is unrelated, probably pulled from some distant corner of the internet, but the clear implication becomes that this is about her. And he’s speaking to her, about her. “I’ve never met anyone else like you.” The clips become his perspective of her. We are seeing her through the eyes of this imaginary man.

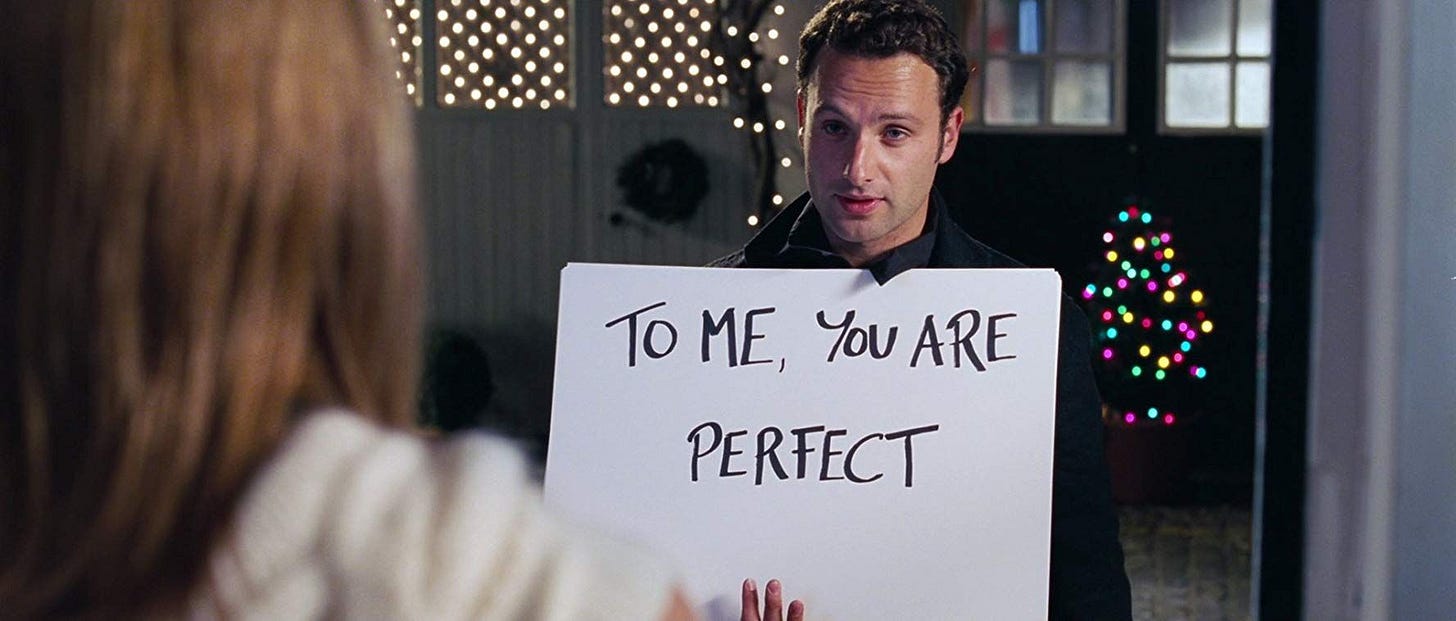

The video is successful because we’re pretty accustomed to this sort of montage. It’s at the end of like, every romance movie ever. We know the language, we know the style. Though the video is literally just a montage of some stranger laughing, doing extremely ordinary things (siting in a car, walking on the beach), we can imbue it with all the meaning of every romance movie we’ve ever watched.

But she made the video as a way of achieving “self-love.” Here, self-love is not obtainable by just watching any old video of yourself; it’s obtainable by editing yourself, by positioning yourself as a voyeur in your own life, by becoming someone-else who loves you. Self-love is voyeurism. Self-love is nostalgia. Self-love is a distance in which you look beautiful.

Quick Note: A feminist reading might say that the main character is an example of internalized male gaze. If I had read John Berger, I might quote him at length here, but I haven’t, so I’ll just paraphrase a paraphrase of one of his more famous ideas—men watch, and women watch themselves being watched. But in this essay, and with this concept, the main character can be a man (or any gender). I think movies like 500 Days of Summer (or anything else with a Manic Pixie Dream Gal) and TikTok Boys make it clear that men also attempt to watch themselves being watched by women. Often, these men are less practiced at this art than women, leading to really “cringe” results—like the entire (wonderfully painful) oeuvre of TikToker Tyler Brash.

There’s tons of songs that do this too—songs that are ostensibly love songs, that are actually about the singer. Patron Saints of @BookNotes_ Taylor Swift and Lana Del Rey do this constantly, especially in their earlier careers. (Lana has always seemed much more self-aware of this than Taylor, her songs usually acknowledge that they are truly about herself, and see the deeply funny “Brooklyn Baby”). My full playlist is below (or here). Not all songs are a perfect fit, but, you’ll get the gist.

For the record, Tiqqun would agree:

However vast her narcissism, the Young-Girl doesn’t love herself; what she loves is “her” own image, that is, something that is not only foreign and exterior to her, but that possesses her, in the full sense of the word. The Young-Girl lives under the tyranny of this ungrateful master.

And:

The Young-Girl gets depressed because she would like to be a thing like other things, that is, like other things seen from outside, though she can never quite manage it; because she would like to be a sign, to circulate without friction through the gigantic semiocratic metabolism.

It’s probably part of why we like social media so much. It does the same thing. We are the editors, publishers and 3rd-person-protagonists of our own lives. We edit our posts with voyeurs in mind, but mostly, we’re our own audience. Sure, we hope other people think we’re hot and have a great life, but we only rarely hope that very specific individuals look at our profile and desire us.5 Rather, we want our lives (and ourselves) to be desirable in a broad sense, which is also to say, to ourselves. Our profiles become what we find desirable.6

The Young-Girl isn’t as worried about possessing the equivalent of what she’s worth on the marketplace of desire as she is about assuring herself of her value, which she wants to know with certitude and precision, according to the thousand signs remaining for her to convert into what she will call her “seduction potential,” in other words, her mana.

Tiqqun has a lot to say about desire, seduction, and sex—a lot that I don’t quite follow. But the gist of it is this: seduction is the primary means by which we evaluate our own and each other’s (very literal) worth.

I’ve been thinking for a long time about this totally wild Miley Cyrus interview from Call Her Daddy. When I first listened to it, I was really ridiculously depressed by how Miley talks about sex as something totally decoupled from pleasure, but also as a core part of her identity.

My identity is related to sex in a much deeper way than my sexuality is. My identity and who I am as a person is very sexual… and who I am as a sexual person, maybe I’m a selfish pyscho, but sex is really about me in my mind. …I think people think of me as a hyper sexual being, but I enjoy sexuality more than I enjoy sex.

She says “identity” when she means “brand.” I don’t think she knows the difference. To be fair, it would be incredibly hard to tell the difference when you’re a celebrity, when your whole life is basically an exercise in branding. Which is what we’ve all signed up for on Instagram.

What’s so appealing about making yourself into a brand? One immediately obvious answer is that a brand is much more controllable than a person—by which I mean, it’s a lot easier to curate your Instagram and decorate your perfectly minimalist/maximalist bedroom than it is to fix your life or stimulate “personal growth.” But I think posting on IG serves a purpose beyond convincing your friends that you’ve achieved picturesque enlightenment; social media allows you to tell yourself who you are.

That Bachelor book I read recently made a nice point about how all the influencers on the show seem to suffer from a disconnect—they are accustomed to being in control, to mediating their lives through social media, to being the sympathetic editor of their narrative/brand/identity. Giving up the control of your narrative sounds terrifying, but these girls seem fearless, naive, almost delusional. Some of them say the cruelest things with total confidence that America will still love them after its all said and done.7 It’s almost like they think they will be able to control their own narrative on a nationally broadcast TV show. They’ve grown too accustomed to thinking of themselves as the main character to realize they could be the villain.

Maybe this is all just classic narcissism, vanity. But I think it’s a little deeper than that—it speaks to a desire for our lives and ourselves to be legible, to ourselves and to others. We want to be understood and loved.

Before I read Tiqqun, I had already been thinking for a while about why we like other people telling us who we are. It’s why we take personality quizzes,8 why we like astrology,9 it’s probably why I signed up for so many sociology classes in college, and Tiqqun would say it’s part of why psychological analysis is so appealing, but it’s also why reading books like Tiqqun’s is fun. It’s why we want to read books and watch movies about people we identify with. We want to be told who we are, by someone who is objective but also sympathetic.

My guess is that we like being told things about ourselves for a couple of reasons. Mostly though, it means someone has noticed us. Someone cares enough to think about and recognize the type of person we are. Like when someone gives you the perfect gift, the pleasure isn’t really even in the object, it’s that the giver knew what type of gift you would like. When people tell us who we are, we briefly become the “main character,” someone who is observed and worth observing. A no-longer-imaginary boy tells us, “I’ve never met anyone else like you, and I don’t think I ever will.” It reifies our own importance in the world. Someone’s taken note of us.

I also think that hearing yourself described is a relaxing mechanism. Or, as Tiqqun puts it, “Relaxing, for the Young-Girl, consists in knowing exactly what she is worth.” We’re very concerned by how other’s perceive us, so to know how someone sees you allows you to briefly, in that moment, put down your guard. You don’t need to preform any more. You just got an Oscar. Take a break. (But it’s only a break. After this, now aware of this quality that outsiders perceive in you, you might preform it even harder. I see this constantly in reality TV stars, who, affirmed for their dry humor or ditziness or whatever, double down on it in the next season of the show. Who me? I’m the ditzy one. Personality becomes a shtick.)

And of course, many of us are our own worst critics. We need an outside voice occasionally telling us to be kinder to ourselves. I do think that’s powerful and nothing worth sneering at. Maybe it isn’t really “main character syndrome,” it’s a God complex. I’m redeemable. My flaws make me perfect. I’m beautiful because I don’t know it. Look how pretty I am.

So when no one is there to tell us about ourselves, we must hold our own mirror. Or selfie stick or whatever.

Tiqqun:

The Young-Girl always-already lives as a couple, that is, she lives with her image.

And more Tiqqun:

…the Young-Girl thinks that she is the object of much more surveillance than she really is.

So, some solutions: My impulse is to like, delete all my social media. But I don’t think that would actually help me. I’m one of those people who writes with an audience in mind even my very private journal. Another solution might be to look for, to admire, and to observe people who seem dissimilar from you, whose problems are not your own (I am once again asking for you to read fiction). Or maybe we should seek grander narratives for ourselves, narratives that don’t photograph well, that aren’t easily expressed or commodified on social media. But those things seem to only address the symptoms of the larger issue. If we’re always looking for reassurance, for absolution, if we’re looking for something we struggle to meaningfully give ourselves and rarely satisfactorily receive from other people, either we find a way to stop having that need, or we find a framework by which we can meaningfully receive those things.

Easier said than done! What consoles me, at least, is that none of this is new stuff we’re reckoning with. Like, religion is one framework by which people find try to find reassurance and absolution (love and understanding), and that’s old as fuck. I haven’t read Romeo & Juliet in years, but I seem to remember a pretty good argument to be made for them being “in love with love” (which is to say, in love with yourself in love) rather than each other. What’s new is just how visible it all is. So while I’m sure Instagram has fried my brain in many ways, our weird-ass uses of it is prolly more of a symptom of the human condition, rather than a symptom of 21st century brain rot.

In that spirit, next week, I’ll be rewriting Mrs. Dalloway from a modern POV. It’s all gonna be one extended montage of Clare Dalloway walking through London, listening to Clairo on her iPhone, and snapping pics of flower stands for her ‘gram. She scrolls past poor Septimus’s TikTok without a second glance.

Til then!

Book Notes

PS. If you made it this far, and haven’t already subscribed, you can do so below! I’ll be emailing you every Tuesday :)

Annnnnnnd let me know if you think I’m dead wrong about all of this:

This is not the original video for this audio. This is mega-TikTok star Addison Rae, who, arguably, is the main character of TikTok.

Also, a quick note for LOSERS who haven’t been on TikTok yet— TikTok allows you to take other people’s audios and use them in your own video.

Tiqqun: “With unfeigned bitterness the Young-Girl reproaches reality for failing to measure up to the Spectacle.”

Popularity is pretty hard to measure on TikTok. It’s a wildly ephemeral platform.

We do, obviously, occasionally post with particular people in mind. Crushes! Exes! Etc.

If I remember Females correctly, Andrea Long Chu might extend this: we become what we find desirable.

To be fair, America might just love them when it is all said and done. They’ll go on Bachelor in Paradise, fall in love, be redeemed. More on that later.

ENFP :)

No.