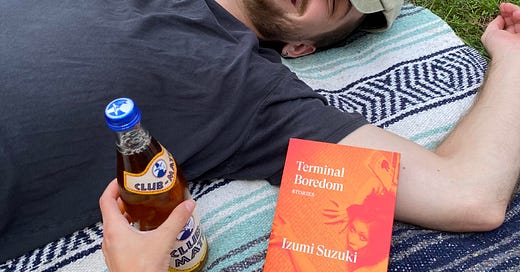

Terminal Boredom by Izumi Suzuki

"terminally boring," a perfect description for most contemporary literary fiction

Hi y’all!

Book Notes—once called the “enfant terrrible of book bloggers” by my dad—is back, with a review of Izumi Suzuki’s short story collection, Terminal Boredom.

Quick reminder to read the “kidney story” in the NYT. It’s narrative is getting more complicated as more info comes out, but it’s a terrific piece of writing regardless. My opinion on it changes with every new person I talk to, but trust me: you will have an opinion.

Speaking of opinions: last week I had drinks with Julie and we agreed that contemporary literary fiction is just. too. boring. All these brilliant, eloquent authors writing gorgeous, quiet, boring, unreadable snoozers. Yawn!

Anyway.

Terminal Boredom is a collection of science fiction short stories by Izumi Suzuki.1 Published thirty-five years after her death, Terminal Boredom is the first time Suzuki has been translated in English. From what I can tell, it’s only posthumously that her stories ever appeared together in a collection—they were originally published in Japanese magazines.

I had never heard of Suzuki before I bought her book on a whim at the Verso sale (not surprising, given the lack of translations), but she was apparently a pretty influential figure for science fiction writers, especially female sci-fi writers, in Japan.

Brief bio from ArtReview:

Izumi Suzuki was born in 1949 under the Allied occupation and came of age during the 1960s, an era of drugs, rock and roll, and nationwide protests in Japan as it was elsewhere. After high school she worked briefly as a keypunch operator at Itō city hall, but soon quit to pursue writing, acting and modelling, working with the controversial photographer Nobuyoshi Araki as well as maverick directors Shūji Terayama and Kōji Wakamatsu. In 1973 she married the free-jazz saxophonist Kaoru Abe, with whom she had a daughter. The couple’s notoriously tempestuous relationship, dramatised in Wakamatsu’s 1995 film, Endless Waltz, ended in divorce in 1977, and Abe died from an overdose of Bromisoval the following year. Suzuki produced the majority of her work, and her best science fiction, in the last ten years of her life, which ended with her suicide at age thirty-six, in 1986.

She sounds—sorry, there’s probably a better way to put it, but let’s be real—cool. A writer-model icon and muse in a “notorious” relationship with a free jazz saxophonist? Photos of her, like the one that appears on the cover of Terminal Boredom, are captivating.

So, I really, really wanted to like Terminal Boredom. I did my best to like it. And for the first two stories, I really did.2

If I’m going to be, like, totally pedestrian, I would say that Terminal Boredom reads like if Ottessa Moshfegh3 wrote Black Mirror episodes. Suzuki long precedes both Moshfegh and Black Mirror, so, more justly, I’ll say she was ahead of her time.

Moshfegh: Suzuki is understated. Suzuki is crisp and cool. She writes about power and gender, ambivalently. This passage from her story “You May Dream“ could be the monologue from R&R:

Like most people these days, I don’t over think things. I’ll go along with whatever. No firm beliefs, no hang-ups. Just a lack of self-confidence tangled up in fatalistic resignation. Whatever the situation, nothing ever reaches me on an emotional level. Nothing’s important. Because I won’t let it be. I operate on mood alone. No regrets, no looking back.

Before me, the world stretches out flat, smooth, and featureless. Gentle and inconsistent.

Black Mirror: You remember that Jon Ham Christmas special “White Christmas” and the dating app episode “Hang the DJ?” Episodes where you know there’s something off, that a twist is incoming, and the twist will totally change the way in which all previous actions are interpreted? That’s the structure of Suzuki’s stories. Not always, but often.

The stories of Terminal Boredom are told mostly through dialog. Often, without much context, a reader will be placed in a conversation between two characters that seems totally normal. But there will be one minor quirk, something that seems so small. After a few stories, you know that this small detail is a sign of a much larger and we are left to wonder in what massive way this world is different from ours.

In “Night Picnic,” the third story of Terminal Boredom, we follow a family of four, who live in an abandoned human settlement in space. They have clearly been alone for a while. The son casually mentions that his sister used to be his brother, until their mom decided she wanted a daughter. Other strange ticks in their vocabulary allude to their practicing specific gender roles and family dynamics they learn from TV shows and books. At the end of the story, we discover that everyone in the family is actually a shape shifting monster who killed all the humans of the settlement.

The stronger of the stories in the collection don’t have twists. Or at least, I don’t like twists.

Let’s look at the first story, which I liked best, “Women and Women.” It takes place in our world, only slightly in the future. A few decades before the start of the story, men began to die out, due to “something called pollution,” and women, long oppressed by men, take advantage of this to institute a matriarchal society, rounding the remaining men up and imprisoning them in “GETOZ” (“Gender Exclusion Terminal Occupancy Zones”), where their inherent “violence and cunning” can harm no woman. Our protagonist is Yūko, a teenage girl who has never met a man in her life.

In this society, no one is allowed to even look at art or music or movies by men or with men in them. Lesbian relationships are encouraged. Often one of the women in a relationship will always try to “emulate what we’re told masculinity was like in the old days,” though this is starting to fall out of fashion with younger generations. Women get pregnant exclusively through IVF. Something is missing. Yūko senses this, and so do we.

By the end of the story, Yūko will meet a boy. And they will have sex—though it’s vague about whether or not this is consensual. Consent is almost besides the point. He will teach her “an unexpected, dreadful truth about human life” and she will learn it “with [her] body.” She learns “an unthinkable truth,” a “dreadful, spine-tickling thing.” It’s life changing—maybe. She begins to pity men rather than fear them, and she begins to doubt her world. But our narrator has no intention of joining a revolutionary group to free men. At least, not “right now.”

This ambivalence, this uncertainty, is characteristic of Suzuki’s commentary on gender and power. Something’s wrong, but she’s not sold on the feminist’s solution either. Her characters are usually found on the precipice, or the seam, between two worlds—these worlds are separated by technology, by ideology, by culture. They attempt to walk the seam, to stay above the fray. Inevitably, they fail, but they always have an eye looking back over their shoulder.

Ultimately, the ending of “Women and Women” is the most hopeful of all of her endings, which is saying something, because it’s fairly bleak, all things considered. This is perhaps what I found the hardest about Suzuki’s writing: after reading the first three stories, I knew each ending would be bleak; I knew the note each story would end on before I read it; I knew the unsettled, ambivalent register; I knew where we would end, I just didn’t know how we would get there.

Some of Suzuki’s writing is so on the nose for today’s concerns, it makes me wonder if the world has changed at all since the 80s. I think part of the reason why her writing seems so fresh is because—although Suzuki’s stories have wild, strange, and brutal sci-fi backdrops—her primary concern is about relationships between people. Like, read this passage from the titular “Terminal Boredom,” narrated by a girl who is watching TV with her boyfriend. It sounds like it could have been written about Instagram:

He was staring at the popstar on the screen. She was probably the one he was truly in love with. I’ve got my own favourite celebrities as well, so I’m well aware that there’s no point in being jealous. It’s just an image, it’s not real—how can you compete with that? And yet, the jealousy is there.

Wow, a mostly positive review so far. Sometimes I find myself writing glowingly of books I ultimately wouldn’t re-read. This is probably for a number of reasons, but I’ll chose the most flattering one: I know good writing when I see it, and I’ll praise it, even if it isn’t to my taste.

And ultimately, Terminal Boredom isn’t to my taste. I think I would have really liked it when I was 22. But right now, like many people, I’m personally tired of muted narrators, of ambivalence, of girls who act nice and sit by the window and think mean thoughts until they snap. That’s not all of Terminal Boredom. But it’s a few stories. And that voice isn’t fun for me anymore.

And that’s part of the problem. Suzuki was ahead of her time, but her stories were translated to English a little after this style of writing stopped being, well, cool. Her style reminds me of what Stephen Marche calls “the pose”—a sensibility and style of writing that we’re all getting pretty sick of (ok, I’m getting pretty sick of it). Marche names Ottessa Moshfegh, Sally Rooney, Ben Lerner and Sheila Heti as primarily examples of the pose, and describes their writing thusly4:

There is not a word out of place. Each sentence passes quality assurance: The sentences are certified, not wrong. The writing of the pose is, first and foremost, about being correct, both in terms of style and content. Its foremost goal is not to make any mistakes. Its foremost gesture is erasure and its foremost subject is social anxiety and self-presentation. One never loses oneself in the writing. Rather, one admires, at a slight remove, the precision of the undertaking.

The same could be said of Suzuki’s stories. Compare that description with this Suzuki passage about a girl visiting her boyfriend’s apartment for the first time (also from “Terminal Boredom”):

HIS (father’s) apartment was fully mechanized. Everything spick and span.

‘This way.’

HIS room was especially clean, airy and pleasant. Seemed like a nice place to spend your time. A video camera was set up in one corner.

‘What do you record?’

‘My daily life.’

‘And you watch it later? Wow, must be riveting.’

‘Sometimes.’ He adjusted the lighting, temperature, and fan.

The guy then puts on a snuff film, which they watch dispassionately, with equal remove. (Very Brett Easton Ellis.) I liked this story a lot, the snide side-eye it seemed to give the reader. The ending is jarring and perfect, the blurring of media and reality is spot on. Sci-fi, especially the very dark, contemplative, and psychological sci-fi explored here, works shockingly well with the understated, simple prose of “the pose.” It allows our understandings and enactments of gender, power, media all to become more strange than the aliens, monsters and futuristic technology that populate Suzuki’s work.

In summary, this book is good! It’s well written! It just didn’t do it for me—“At least, not ‘right now.’” If you read sci-fi or writer of “the pose,” it’s an interesting to see how the two are combined here. I hope more of Suzuki’s work is translated soon, it definitely deserves to be.

Why are there so many ambivalent female narrators? I shake my fist at the sky after writing what’s ultimately a pretty ambivalent review.

Oh well.

Fall is treating me very well, though I’m very busy! I’m listening to this band of 23-year-old boys who dress and write music like Brooklyn hipsters from 2006. I’m stacking all my most impressive books by the foot of my bed, and refusing to read them. I’m learning about Gamer Gate. I’m repeatedly wearing the same outfit, a black sweater with light brown corduroys. People are starting to notice.

kisses,

Book Notes

If you buy a book through my BookShop links, I’ll get a small commission.

TL;DR—I really recommend reading that ArtReview article I just quoted. It reviews the book in regards to its cultural context, something I know nothing about.

I kinda dread writing reviews of important, beloved books that I’m unmoved by. Like, I was totally indifferent to The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and this indifference ironically led to a full blown existential crisis. As confident as I am in my taste and my judgement, I can’t help but look back at my 2 star review of The Sound and the Fury from high school and cringe. NGL, I feel a little sick even admitting that my 15-year-old self was so dumb. Who did I think I was?

Well, I was fifteen, reading a challenging book that I didn’t really understand. But now, when I read these important, beloved books that I’m unmoved by, I worry that, like my 15-year-old self, I either don’t understand the book, or I don’t have the context to understand why it’s important.* But also like, this is my blog. This is my little public diary. This is where I write about my experience with books. So I say dumb things here all the time. And I change my mind all the time. That’s cool. I forgive 15-year-old me for being a dumbass, because I’m a dumbass here constantly. It’s fun. That’s why—I assume—you are here.

So, here’s the heads up: I know nothing about the history of Japanese science fiction, in fact, I read very little science fiction at all, and I’ve read even less fiction by Japanese authors, so maybe I’m just being straight-up ignorant by writing a review that’s like, “meh.” I felt the same way when I was reviewing Blood and Guts in High School—like, “I’m not equipped to contextualize this book in its historical and cultural moment, but fuck it, I guess I’m reviewing it anyway.” I’m not the ideal reviewer for this book, but most readers won’t be either. We’re in this together.

Wow, this all sounds like I’m gearing up to, like, totally pan the book. I’m not at all! I just didn’t love it!

*footnote to the footnote* FOR THE RECORD: I don’t have this problem with contemporary lit. Like, I’m totally fine saying that Anthony Doer’s All the Light We Cannot See was sentimental purple prose; that Donna Tartt’s The Secret History was overwritten, corny, and lacked any memorable characters; that Sally Rooney is Just Okay; that My Year of Rest and Relaxation should have been a short story (more on that soon).

To be fair, I’ve only read My Year of Rest and Relaxation. But whatever.

lmao

It’s been hard for me to find Japanese literary and/or experimental fiction that isn’t boring, from Haruki Murakami on down.