Hi y’all!

Good God, it’s cold in New York right now!! Somehow though, George and I managed to make it out to the Fuccboi book launch, hosted by Forever Mag at TV Eye. The place was packed—even the bouncer was shocked by the turn out. “This is for a book?” He asked the girls in front of us in line. “This is more people than come out for music.”

And it was one of the best readings I’ve been to in a while! The energy was high, the readers were weird, and there was a great DJ who played disco for a few hours after the reading. I now firmly believe that all readings should end with a disco set, or like maybe they should start with one.

We liked this song the best.

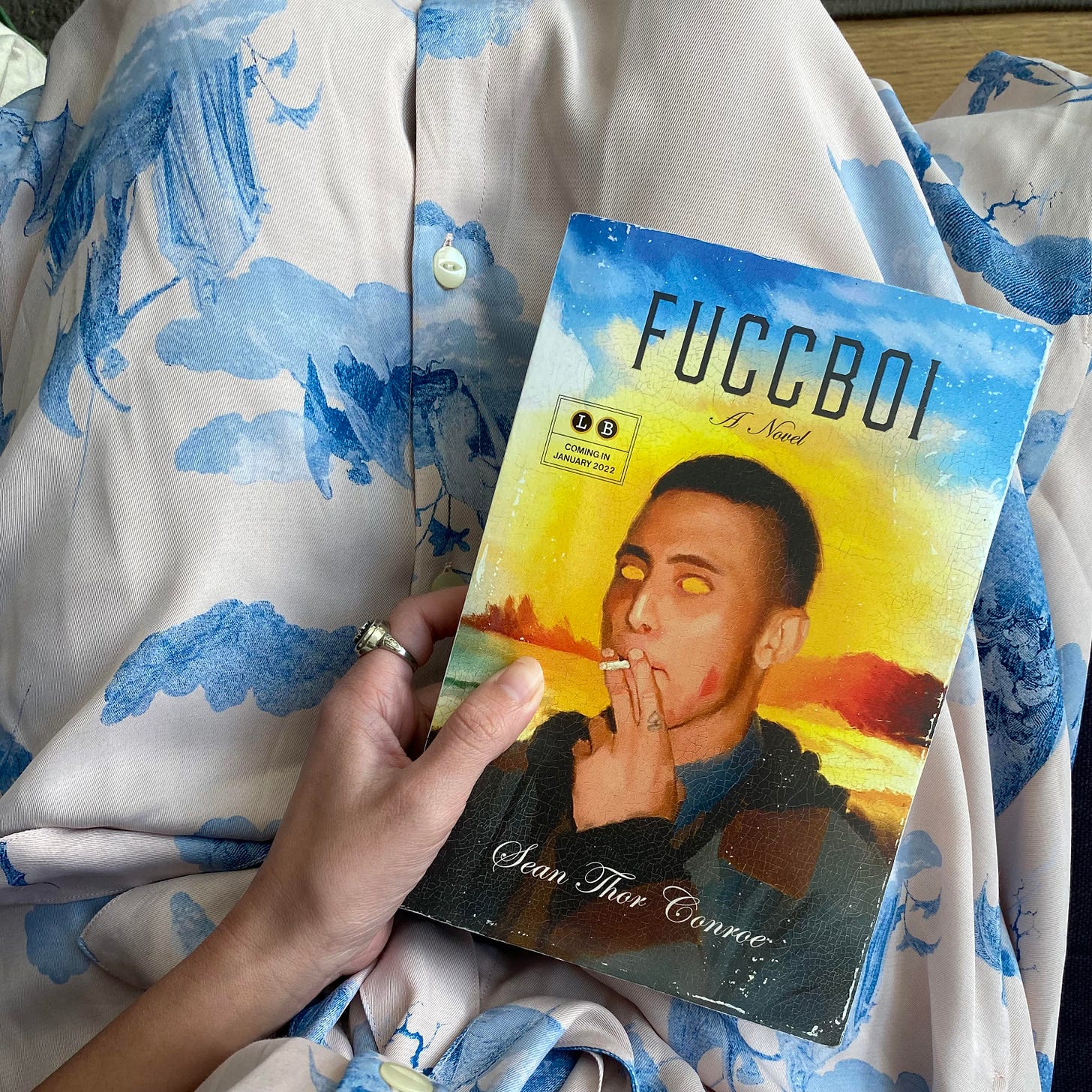

Anyway, I’m so excited to write about Fuccboi by Sean Thor Conroe, which, full disclosure, my good friend Julie represented. This doesn’t make me biased though, because I have great taste and I’m always honest. The book came out last Tuesday and you can buy it here.

Fuccboi is, apparently, a love-it or hate-it book. I don’t wanna sound too online, but it looks like the book is clearly dividing, mostly along the lines of: “If you get it, you get it; if you don’t, you don’t; if you know, you know.” And honestly, maybe I’m jealous if you don’t get Fuccboi. Because if you don’t get it: either you’ve never felt like a total loser, or you’ve never met a guy like the protagonist Sean.

The protagonist of Fuccboi shares the same name and many of the same autobiographical details as the author. Someone else can write (and someone definitely already has written) about what it means to give your protagonist your name and bio, but that’s not super interesting to me. It’s fiction. Anytime I refer to Sean from here on out, I mean the character, not the author.

Soooo. Fuccboi follows Sean, who’s drifting through his post-college twenties delivering Postmates, missing his ex-girlfriend, and watching the world close in around him. He’s still living in Philly, where he went to college and where his ex still lives too. He’s reading and trying to write his “Walk Book,” which chronicles his failed-walk across America (he got to Denver). He’s broke. He’s got a podcast and a SoundCloud. He’s got a humanities degree. He’s developed a terrible, debilitating, eczema-like skin condition that doctors don’t know how to treat. We like him, sometimes despite himself.

The year is 2018, but if the novel was set a year or so later, we’d probably describe Sean as a softboy rather than a fuckboy. A fuckboy is a charming, good looking, womanizing narcissist, often presenting as some iteration of “bro”—finance bro, lax bro, whatever. The softboy is the sensitive and nominally self-aware fraternal-twin of the fuckboy. Or maybe he’s just a specific subgenre: he’s the art bro. He’s Sean. Sean reads Elena Ferrante. He’s tried polyamory. He’s “about That Art Life,” and he’s pleased that his roommate is a woman, because it “immediately established [him] as non-predatory.”

Fuccboi is written entirely in his voice.

I host a monthly “Books Club” that essentially functions an “Adult Book Report Hour.” At the last Books Club, I spoke about Fuccboi, but it presented a challenge: I would sound rediculously, unimaginably dumb reading aloud from Fuccboi.

Here’s a sample:

After automous bae and P dipped, lowkey panicking.

Not digging being in here all gowned all fucked.

Needed to rally.

To get tf out.

”K first thing next morning gonna.”

Tried to conk, telling the nurse Kill the light.

Lay on my side, tryna calm my tits but sweating scratching.

That’s from while he was in the hospital for his skin condition. The below is from a chapter while he’s still Postmating.

I was a modern-day hunter, riding my horse-bike around, delivering food to these basic fucks unable not only to make it themselves but even pick it up; hunting for food—foraging for nuts—at night, when safe from emotional predators; loving all my baes equally, according to the non-ownership-based polyamory of matriarchal yore.

This voice! This voice that I can hear so clearly in my head, a voice that I heard from so many 19 year-old white boys in college, a voice that is academic, kinda internet-poisoned, and bro-ishly appropriative of black slang. It sounds kinda like how Billie Eilish talks. I was trying to find examples on YouTube, but it was taking too long to find the right one. “If you get it, you get it”—if you’ve heard it, you’ll recognize it. If you haven’t, a lot of Fuccboi may be totally unintelligible to you.

Anyway, I couldn’t read it aloud because, as y’all know, I sound like a braindead sorority bitch most of the time.1 Which, to be clear, I’ve always liked about myself, and it’s something that I also try to replicate in my own work—which is probably clear to you by now, ha. Mimicking your own speech, your dialect, your voice, in your writing is respectful of language itself. In writing with the voice that all my friends and I actually use, I’m taking it seriously. I’m saying there’s something interesting and cool and worthy and maybe even beautiful in all of our text speak and cliches and hyperboles we use. Using colloquial language or dialects in literature isn’t controversial or anything new, obviously. I’m just saying, I can’t think of many serious novels written in the voice of a bro.2

This is all to say, I really really liked the voice of Fuccboi. I really felt it, and it was exciting to read. It felt very unique while capturing a way of speaking that’s so familiar to me. I loved it.

Unsurprisingly for a book called Fuccboi, much of the novel is focused on Sean’s relationship to women. It’s fraught, obviously. It’s even more complicated by all the lib fem discourse that’s become a second language to Millennials and Gen Z. Sean says he wants to “evade the paternal stance of unfeeling decider/owner,” believes that communication can solve all relationship ills, and is concerned about where “paternal impulses” might lead him. But mostly he’s angry that the women in his life seem to “effortlessly” “have their shit together,” that they have “no issues integrating themselves economically/socially,” and that they are the gatekeepers to so many things he wants—sex, love, career success. And of course, because he’s well versed in feminist arguments, he’s also a bit embarrassed and disgusted by his anger. It’s a weird sort of double think that’s self-awareness gone rotten.

Over the six months after I agreed to work on my Walk Book with editor bae, I cut—nixed, snipped—every savage, ugly, testosterone-fueled, shameful thing it had been the most difficult to write.

Sean calls all of the women in his life (except his mom and sister) some variation of bae—ex bae, roomie bae, side bae, editor bae, even derm bae. He calls his closer male by their name or initial, but casual friends get the “bro” treatment. TBH, I found the whole bae thing a little too on the nose, but its dismissive categorizing of women is also kinda perversely helpful. We don’t learn much about any character in the novel other than the protagonist. His guy friends—E, V, N, among others—appear sporadically, and are hard to keep straight. Ironically, the descriptive name like “editor bae” is far more distinctive than a more personal, humanizing initial.

The only people who actually get names are the writers that Sean admires—Shelia Heti, Eileen Myles, Karl Ove Knausgaard, among others. Fuccboi is an unexpected reader’s diary, and I’d say more about that, except we don’t have the same taste and I haven’t read most of the writers he cites. Whoops!

I have read Hunger by Knut Hamsun though. I read it in high school, over a decade though, so excuse me if I’m getting things wrong, but the parallels between the two books seem obvious.3 Hunger is a semi-autobiographical novel, written in the first person from the perspective of an unnamed narrator. Like Fuccboi, there’s no real plot, rather, we watch the protagonist move throughout the city, trying to find work, to impress his peers, and to write. He’s broke and starving and alienated from the city and society in his poverty. There’s a girl that he’s obsessed with, but he calls her by a made up name and refuses her help. No one will publish him, no one will even hire him for manual labor, and his body is decaying. Both Sean and Hunger’s protagonist are concerned with dignity (and masculinity) to the point of self-sabotage. Hunger’s protagonist blames God while his own pride and society are truly at fault; Sean blames society, but all the wrong parts—getting “lowkey redpilled” on wage gap discourse, when he doesn’t even have a wage to begin with. Like I said, I read this book yearsssss ago, so I can’t really draw out more than surface similarities, but I’d be interested in reading Hunger again in light of Fuccboi.

Conroe’s sentences, paragraphs can be funny, can be compelling, can be gross, and can make your groan. But he’s the best at the scene level! The second chapter has the only good party scenes I’ve ever read in any book. Each section is so, so painfully accurate and perfect. Sean meanders—through physical labor and parties, to doctors offices, around the East Coast and twice to California, in friend’s cars and in a van, working odd jobs and meeting strange people. He’s a loser who is unwilling to let go of the past and the unfulfilled promises it seemed to make, but he’s also terrified to revisit the past in any meaningful way. He exists in this strange sort of limbo. It makes sense that many of the books early chapters take place after midnight.

Ok, time to admit: I first read excerpts from Fuccboi online, and I wasn’t super impressed. But things almost instantly changed when I had a book in my hand.4 Fuccboi—whose language is very of the internet, whose line breaks could mirror tweets and texts perhaps more than line breaks in poetry—doesn’t really work on a blinding white screen.5 The line breaks can become overwhelming, the scroll endless, the voice too familiar. Unlike viral Twitter threads though, Fuccboi isn’t full of really catchy, one-line zingers. And because of this, Fuccboi can be uncharitably excerpted, which is probably pretty clear by now, if you’ve seen that one page that people are mocking on Twitter.

Honestly, I’m pretty sure most of the people making fun of the book are more jealous about the big advance that Conroe got. The book is about someone whose hopes and promise for the future feel grim and small and impossible; the author’s success, these critics seem to say, disproves “the idea” of the book. I have a feeling that if this book was published by an indie press, like it was originally supposed to, the same people who’re critiquing it now would be praising it.

What makes this feel particularly obvious is that I haven’t read any criticism of the length, which is its most obvious flaw. If I were the editor of Fuccboi, I would have cut this book down by probably by 100 pages. It’s currently a little over 300. While the prose is exciting and lively throughout; there’s no plot, some scenes basically repeat, and the sentences can be loose and freewheeling—all of which calls for a tighter and more economical final manuscript, so that the best scenes can really shine. I only mention this because I’ve seen some really stupid critiques of the book (uh, Gawker’s)6 and it’s shocking to me that no one noted the obvious.

My favorite parts of the novel describe Philadelphia and how a city can feel like it’s closing in on you. I don’t know if New York could ever feel that way—it’s too big and impersonal. But when you live in a small city for a few years, and when you’re depressed, and when you’re trying to avoid anywhere that has too vivid memories (good or bad), and your ex only lives a few blocks away, and you’ve aged out of your favorite bars, and your friends have all left for different coasts and bigger cities, when a city seems to offer no new possibilities—Fuccboi describes that kind of anxiety so well.

Philly, by foot, over the two years since I’d returned, had been reduced to like three places.

Three routes.

Especially so lately, now that I could no longer bike.

Everywhere with even the faintest whiff of a pre-walk ex bae memory too treacherous, unless whizzing past.

Philly had become: along 41st to the Sunoco on Baltimore (cheapest tobacco in town), to pit stop at Clark Park there for a bench cig, and back—detours off of which included the Fresh Grocer, CVS, roomie bro’s and, now, the dental school.

To the Wawa SE of my spot, that I rarely walked to since it was ex-bae’s way.

And…

Wait yeah.

That was basically it,

That was Philly.

Also there’s a map of Philly at the end! Every book should have a map!

Alright, here’s another link to where you can pick up Fuccboi. I’ll get a small commission, blahblah, you know the drill. I hope y’all do read it because I want to know your thoughts.

Finally, I’ll leave you with a quote that also perfectly describes my relationship with this lil blog and my faithful readers:

While roomie bae bustled around the downstairs living/kitchen area, I tried to do what I used to to ex bae.

What I did to all my female friends/lovers.

That is, ramble my unformed thoughts about some new idea, treat her like my sounding board, and then, once I’d finished, had nutted (intellectually), sit there and wait for her to tell me my ideas were in fact fully formed.

I’m waiting!

Hugs & kisses,

Book Notes

Which might be the female version of the way that Sean speaks, but it has it’s own quirks. Like saying “like” every other sentence, equivocating constantly, dropping unrelated personal anecdotes unnecessarily, etc.

Maybe Fraternity by Benjamin Nugent, but it certainly doesn’t get as deeply voicey as Fuccboi.

When I was 19 I recommended Hunger to a group of lit bros (who spoke exactly like Sean) and they laughed at me “Knut Hamsun? NUT Hamsun.” And then a few weeks later, one of them was assigned the novel for class, and he gushed about how great it is to me at a party.

And not just bc I’m a slut for ARCs.

lol, hi

Not gonna dwell on that review bc I thought it was pretty dumb, but I laughed out loud when the critic says (1) that he and his friends have never worried about how woke or un-woke they appear, (2) that this is somehow relevant to the book at hand, and (3) that Sean isn’t representative of millennials because he’s far too weird and isolated, unlike the protagonists of all the popular millennial books by women.

….I’m sorry, has this man read ANY of those popular millennial books by women? The primary example is about a woman who literally never leaves her apartment and drugs herself in an attempt to sleep through a year!!!!!!!!! Like?????? Huh?