Hi y’all,

I wrote this essay in the spring of 2017, just before I graduated from college, and published it in a literary magazine that nearly ended my friendship with Jesse. I’m re-publishing it here because it describes an anxiety that I still have today, and also because I think this essay is probably the first “real” Book Notes essay. By the time I wrote this, the Book Notes Instagram was already a few months old, but I was mostly just posting pictures of my books, not full reviews. Writing this essay made me realize that a review wasn’t a school paper—there was room for my voice and my life in what I wrote.

I wrote this essay four years ago (when I was 22) about the summer four years prior (when I was 18). Now that I’m 26, it seems like a good time to check in on it again.

Also: I still love this book.

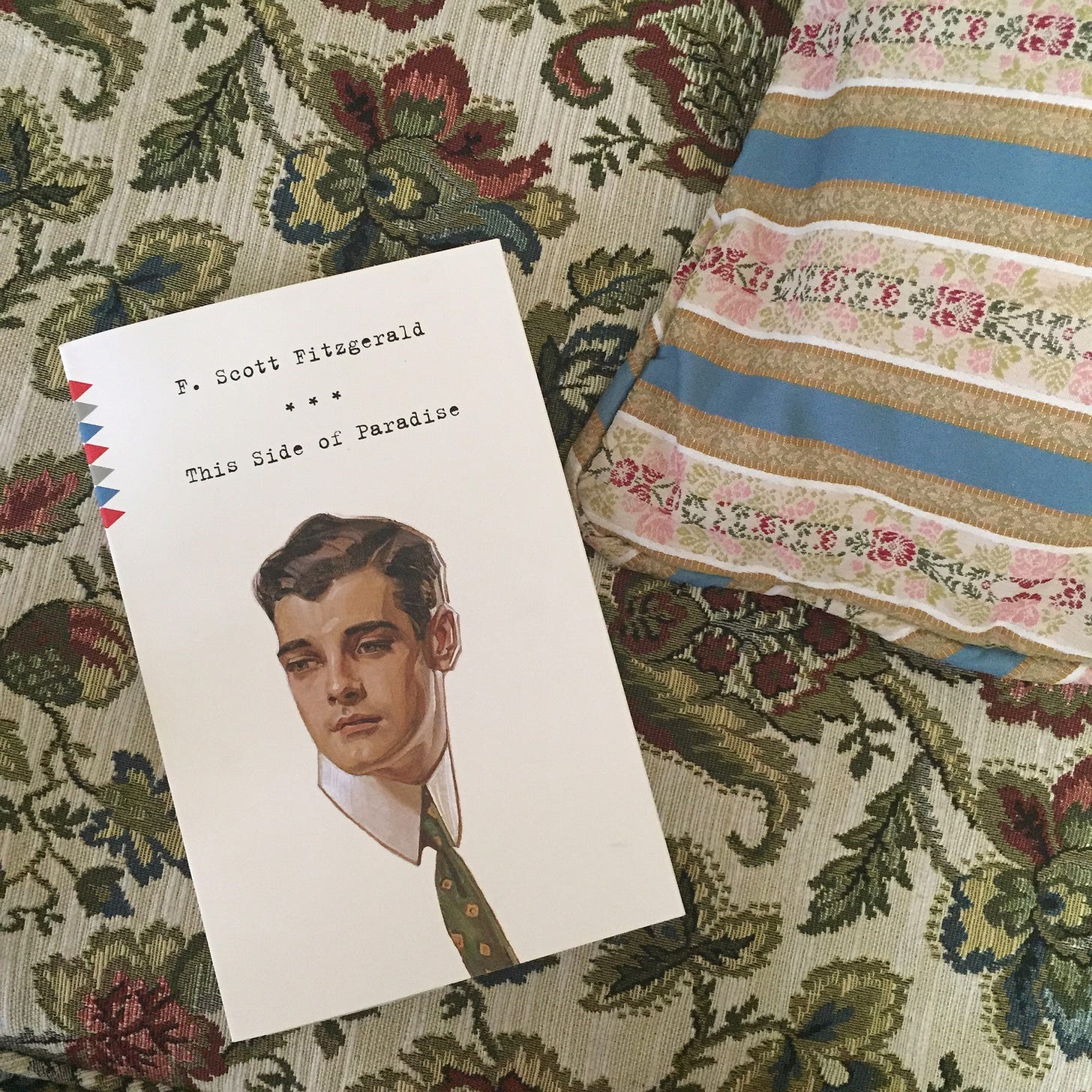

I spent the summer before college working at an away camp in Tennessee. For a month, I lived in a cabin with a dozen thirteen-year-old girls and stood as a sweaty lifeguard on the dock of shallow lake. During my rare free time, I tried to finish all of the books that I had been assigned, but never actually read, during high school English class. The list was embarrassingly long; I had skated through high school on a combination of SparkNotes and the understanding that teachers wouldn’t pay much attention to me if I turned in work regularly. And so, on the eve of my 19th birthday, I found myself reading F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise by flashlight on a bunk bed in the middle of the Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee.

The story behind the novel’s publication was just as exciting to me as the novel itself. In 1919, Zelda Sayre broke off her engagement with twenty-two-year-old Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald. He didn’t make enough money, and seemingly never would. Fitzgerald was undeterred, and set to work on his novel (versions of which had already been twice rejected by Scribner’s) with the hope that upon its publication, Zelda would agree again to marry him. This time, he hurriedly cobbled together short stories, poems, a one act play, and his previous novel “The Romantic Egoist” into one disjointed narrative. This Side of Paradise was published in 1920. He and Zelda were married a week later.

It’s a sloppy first novel. The seams of Fitzgerald’s patchwork are immediately visible—almost two hundred pages pass before stage directions are suddenly introduced, a brief interlude is composed only of letters and poems, and the story itself is clearly made of several episodes rather than a linear plot. Yet Fitzgerald’s sharp wit and eye for detail make this unruliness seem playful and fresh, rather than merely haphazard. Like many coming-of-age stories and debut novels, This Side of Paradise is an exploration of youthful folly—both of the protagonist and the author. The immaturity of the author actually makes the novel more compelling: it’s the work of a young writer circling a message he can’t quite articulate, and surprisingly, the novel is all the better for it. In both subject and form, This Side of Paradise is accurate because of its uncertainty—at eighteen, I understood the fragmented impulses of This Side of Paradise much better than the clear-sighted skill of The Great Gatsby.

The semi-autobiographical protagonist Amory Blaine is vain, lazy, convinced of his own genius, and prone to statements like, “I hate to get anywhere by working for it. I’ll show the marks, don’t you know.” And yet, he is also charming, imaginative, and occasionally self-aware. At Princeton, he befriends the few of his classmates who he takes to be smarter than himself, though any time they assert their talents, he sulks. He falls in and out of love with debutantes who enjoy shocking their peers with their cigarettes and their freely-given kisses. He pursues wealthy girls who have a tendency of making scornful declarations like, “It’s so hard to find a male to gratify one’s artistic tastes.”

Moments of growth are all the more harrowing for their brevity. At Princeton, Amory spends his nights alone, wandering the campus. One night, lying in a quad and gazing up at Princeton’s Gothic spires, Amory realizes his own “unimportance…except as the holder of the apostolic succession” and this “idea became personal to him.” This epiphany won’t change his character. In This Side of Paradise, self-knowledge is fleeting and treated as momentary anxiety. And despite his resolution to work hard at Princeton, Amory finds there are better things than school; after all, there are parties to attend and debutantes to kiss.

At eighteen, I knew that Amory was selfish at best and amoral at worst, but he and the other characters in This Side of Paradise possess a candor and glamour that I admired. He constantly worries that Princeton is “conventionalizing” him, that he will “lose his personality;” I thought of my own stifling Catholic high school. A girl compliments him on his “keen eyes” and he immediately tries “to make them look even keener;” I too had a silly tendency of posing in hopes of catching the attention of handsome strangers. When describing a childhood friend and future love interest, Amory thinks, “She had gone to Baltimore to live, but since then she had developed a past.” I scribbled it in my journal—it was so fitting, I hoped, for the adventure I was about to have. Amory’s downfall seemed to be an avoidable footnote to an otherwise desirable story, perhaps just an accident of the sketchily rendered novel, not at all a natural result of his laziness and egoism.

I won’t lie; part of me still resonates with Amory’s romance and rebellion. I don’t regret the nights of college that I spent sneaking onto rooftops, ignoring work to gossip on a friend’s bed, attending parties and leaving parties with boys who soliloquized on Marxism, but who had embarrassing affinities for their fraternities. And I understand now what Amory means when he thinks to himself after leaving Princeton, “I don't want to repeat my innocence. I want the pleasure of losing it again.”

But as I prepare to graduate from college, This Side of Paradise no longer seems like the enticing literary proposal that I believed it to be at eighteen. At twenty-two, only a year younger than Fitzgerald was when he wrote the novel, I think if I were Zelda, I would be wary of my fiancé. Different scenes in This Side of Paradise draw my attention now. When Amory realizes his own unimportance while lying in the middle of a Princeton quad; I remember the nights in the library that I swore I would work harder—next semester. When Amory drops most of his clubs in a sudden fit of apathy; I think of all the activity fairs I skipped, content with just my hour on air at the student radio. And maybe it is just pre-graduation nerves, but when Amory realizes too late that his hardworking friends have “discovered the path he might have followed;” I can’t help but think of that pile of unread books, still growing on my bedside table.

You can purchase This Side of Paradise here. I’ll get a small commission.

More soon.

xoxo

Book Notes